The month of Shevat brings tools to address gluttony (לעיטה), a trait that is closely related to envy which is a frequent precursor to sinat chinam (baseless hatred). HaShem is the master of timing. As the war enters its phase-2 and we settle a bit more into normalcy, there’s the danger of settling back into our bad habits as well. It’s going to take a conscious commitment to preserve the precious upsurge of national unity that has been our strength for these difficult months. A verbal commitment is not enough to break a multi-millennial habit. It is a spiritual practice that will take concrete efforts to sustain its change. The stakes are high.

HaShem fulfills all the mitzvot,[i] including the mitzvah of tefillin.[ii]

Nahman b. Isaac said to R. Hiyya b. Abin: “What is written in the tefillin of the Lord of the Universe?” R. Hiyya replied:

וּמִי כְּעַמְּךָ יִשְֹרָאֵל גּוֹי אֶחָד בָּאָרֶץ

“Who is like Your people Israel, a nation, singular, on earth.[iii]

[And what is written in our tefillin:

שמע ישראל הוי”ה ﭏהנו הוי”ה אחד

Hear Israel, HaShem our God, HaShem is ONE.]

HaShem declares our singularity and we proclaim Hashem’s. Israel’s mission is to model the oneness of Divinity to the world—to demonstrate that it’s possible (even preferable) to have a diversity of opinions and still cohere in oneness.[iv]

King Solomon declares that a king’s greatness is in proportion to the size of his kingdom.

בְּרָב-עָם הַדְרַת-מֶלֶךְ

In a multitude of people is a king’s honor…[Mishley 14:28]

Rav Tsadok qualifies this assertion by clarifying that this does not refer to His population census. G-d’s greatness does not derive from the number of his subjects. Rather, implies R. Tsadok, it refers to the multitude of opinions, priorities, personalities. distinctions and specialties of his citizens that all manage to peaceably coexist because of the king’s embrace of complexity and commitment to paradox.

There is no glory in multitudes, when they are unable to think for themselves or tolerate diversity. Despite their impressive numbers they are really just a mob.

The obligation of communal unity (as expressed by the verse in HaShem’s tefillin) is fulfilled by the mitzvah of “loving one’s neighbor as oneself.”[v] Or, as reformulated by Hillel:

“What is hateful to you, don’t do to another. That’s the essence of Torah; the rest is commentary.”[TB Shabbat 31a]

The Talmud is clear: Our failure in this department—our susceptibility to sinat chinam (petty hatred toward our fellow Jews)—has caused our greatest tragedies. The destruction of both Temples and our multi-millennial exile persisting till this very day are the bitter fruits of our stiff-necked, self-righteous intolerance.

Why was the second Temple destroyed, seeing that in those days people were occupying themselves with holy deeds—mitzvot, Torah study and exemplary charity? They had a lot of merit going for them. The answer is that, even so, baseless hatred was rampant [to an intolerable degree]. This teaches that sinat chinam is even more deplorable than the cardinal sins of idolatry, promiscuity, and murder. And what about the first Temple? Was there baseless hatred there as well? Yes, says R. Eliezer. Also there…the people would eat and drink together and then [afterwards] stab each other with verbal barbs [driven by baseless hatred]. [Yoma 9b]

אֲבָל מִקְדָּשׁ שֵׁנִי שֶׁהָיוּ עוֹסְקִין בְּתוֹרָה וּבְמִצְוֹת וּגְמִילוּת חֲסָדִים, מִפְּנֵי מָה חָרַב? מִפְּנֵי שֶׁהָיְתָה בּוֹ שִׂנְאַת חִנָּם. לְלַמֶּדְךָ שֶׁשְּׁקוּלָה שִׂנְאַת חִנָּם כְּנֶגֶד שָׁלֹשׁ עֲבֵירוֹת: עֲבוֹדָה זָרָה, גִּלּוּי עֲרָיוֹת, וּשְׁפִיכוּת דָּמִים. …. וּבְמִקְדָּשׁ רִאשׁוֹן לָא הֲוָה בֵּיהּ שִׂנְאַת חִנָּם? …וְאָמַר רַבִּי (אֱלִיעֶזֶר): כן אֵלּוּ בְּנֵי אָדָם שֶׁאוֹכְלִין וְשׁוֹתִין זֶה עִם זֶה וְדוֹקְרִין זֶה אֶת זֶה בַּחֲרָבוֹת שֶׁבִּלְשׁוֹנָם.

Disputes are inevitable in a free society. The challenge (says R. Tsadok) is to not let machloket (passionate disagreements) degrade into milchama (war), where everyone is pressed to choose a side and prove loyalty by shunning their disputants even to the point of not “intermarrying” with them. Fracturing escalates to schism and then devolves into civil war, a scenario painfully documented in our Biblical and Talmudic texts.[vi]

HaShem, anticipating this fatal flaw, embedded a safety mechanism into the providential influence He exerts upon our Jewish nation. It does not dismiss our wrongdoings, but it does preserve our peoplehood by designing the world in such a way that our schismatic tendencies invariably instigate a survival threat from without, that forces us to react, regroup and rebond.

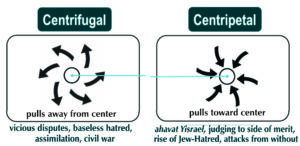

It seems that when Israel starts to spin out, and their centrifugal tendencies threaten to override their centripetal. commitments, suddenly, mysteriously, Jew hatred raises its ugly head. In the last hundred years alone, there’s been pogroms, a holocaust, a perversely cruel jihadist massacre, along with Israel’s 75-year-long existential, war of independence.

centripetal. commitments, suddenly, mysteriously, Jew hatred raises its ugly head. In the last hundred years alone, there’s been pogroms, a holocaust, a perversely cruel jihadist massacre, along with Israel’s 75-year-long existential, war of independence.

And so it’s been for millennia: we thrive until centrifugal forces (i.e., dispute and/or assimilation) threaten our coherency as a people, at which point a survival threat arises from without, reawakening our commitment to the tribe. Centripetal forces then come to the fore and we band together doing whatever’s necessary to survive as a nation.

The Torah anticipated this problem—the danger of our self-destructing through unbridled machloket—and conveys HaShem’s prescient solution in a verse from Devarim that describes our conquest of the Promised Land. The Israelites, having wandered forty years in the desert, are poised to enter, and HaShem prepares them for a slow and difficult influx [Deut. 7:22].

וְנָשַׁל יְי א-ֱלֹהֶיךָ אֶת-הַגּוֹיִם הָאֵל מִפָּנֶיךָ מְעַט מְעָט לֹא תוּכַל כַּלֹּתָם מַהֵר

HaShem, your G-d, is not going to remove your enemies from before you in one fell swoop. Rather, your conquest will proceed slowly, very slowly….

And why is that? The verse goes on…:

פֶּן-תִּרְבֶּה עָלֶיךָ חַיַּת הַשָּׂדֶה

So that the wild beasts do not multiply [in the vacuum that would result from the absence of human settlement.]

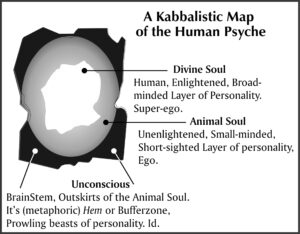

That’s the pshat. But as below so above. These carnivores prowling at the fringes poised for attack if not checked by human settlement…these wild beasts, says kabbala, are actually the unenlightened layers of our own souls.[vii] We all have a nefesh Elokit (a Divine soul) whose joy is to do good, serve truth, dissolve ego and merge with the Divine. And we all have a nefesh bahamit (an animal soul) that pursues creature comforts like dominance, wealth, territory, mating and power. No blame. This nefesh bahamit, is our survival instinct. Its job is to preserve life and protect the ego.

Yet, the animal soul’s dog-eat-dog worldview often clashes with our self-image. The more “civilized” we become, the more this antisocial “beast” gets relegated to the hinterlands of our psyche. Out of sight, out of mind we imagine that we’ve transcended its aggressive temperament.

The Book of Eicha, referring to Jerusalem, reads: “טֻמְאָתָהּ בְּשׁוּלֶיהָ (Her impurity is in her hems),”[viii] meaning her outskirts. Similarly, the hem of our soul refers to its nether reaches—its unconscious layers—the part of ourselves that we haven’t yet faced, partly because our consciousness hasn’t penetrated there yet, and partly because we’re ashamed of its coarseness and suppress its existence.

The Torah conveys (through metaphor) that these brutish impurities, banished to the outer edge of our psyche are the wild beasts that HaShem is concerned about, that need to be kept in check by, strangely, keeping enemies around until we are ready, really ready, to be done with them.

Why? Because there is a constant stream of urges emanating from the “hem” of the animal soul pressing us to satisfy its short-sighted cravings. And as the Tanya explains:[ix] There are two ways to handle these unruly impulses: We can resist them (אתכפיא) or we can sweeten them at their root and divert them toward good (אתהפכא). Obviously the latter is the ideal, but it requires a level of mastery that only comes with a lifetime of spiritual work. In the meantime, we need to practice containment/aschafiya—to sort through our impulses, and only act on the good-serving ones.

Why? Because there is a constant stream of urges emanating from the “hem” of the animal soul pressing us to satisfy its short-sighted cravings. And as the Tanya explains:[ix] There are two ways to handle these unruly impulses: We can resist them (אתכפיא) or we can sweeten them at their root and divert them toward good (אתהפכא). Obviously the latter is the ideal, but it requires a level of mastery that only comes with a lifetime of spiritual work. In the meantime, we need to practice containment/aschafiya—to sort through our impulses, and only act on the good-serving ones.

But the beast needs its outlets. It must have opportunities to express its wild self (for example, through sports, nature walks, political debate/protest, competitions, dancing or the vicarious emotional catharsis of movies, etc). Otherwise its frustration will lead either to depression or to unpredictable outbursts that leave a lot of messy fallout in their wake.

And, of course, one of the most sanctioned outlets is to direct its aggression toward an enemy (real or imagined) that is trying to harm us. On one hand the enemy poses a threat which legitimizes an aggressive discharge, and on the other hand, this instigates a bonding experience for the group, nation, or even couple that feels besieged. It is well-known that a shared enemy exerts a bonding influence upon society.[x] The free-floating aggression of its members gets directed outward, toward the scapegoat, and since the aggression is safely and “honorably” discharged, the people are moved to express their warmth and loyalty to each other.

In the absence of an enemy the aggression, which still needs an outlet, will focus upon targets within the community: neighbors, competitors, political rivals, minorities or the differently religious. Unchecked internecine strife can spiral into civil war. The danger of domestic hostilities is even greater than the threat of war from without. When internal loyalties crumble and infighting escalates, a society splinters and self-destructs.

And so, on one hand, we long to be free of our enemies—they are our greatest anguish… the primary obstacle to quality of life. If they would just disappear, we could finally focus on our soul work instead of always getting sidetracked by the need for self-defense. That is what we believe. That is what we say to ourselves…but, in this verse, HaShem informs us that it is not so simple. The enemy provides a safe target for the aggression of our still-unrectified animal souls.

In this verse, HaShem conveys that we are not ready to be free of enemies. There are still too many untamed “beasts” prowling at the edge of our psyche. HaShem is letting us know that we would tear each other apart if we would lose this “acceptable” outlet to vent our aggressive drives.

The Torah is informing us that sinat chinam is driven by these “beasts of prey” (these emissaries of the ego) patrolling the psyche’s buffer zones to keep ego-discomforts at bay. They are groomed for the job. Hyper-sensitive to the slightest insult their reflex (and expertise) is to punish, discredit or silence anything that disturbs the ego’s peace. They are called beasts because they are managed by the brainstem, not the cortex. They strike faster than the speed of light.

Rashi defines nachas as the satisfaction of “voicing a request and having our will fulfilled.”[xii] That is an ego-gratifying scenario, whereas its opposite is shaming. When we make a request and our will is thwarted, the ego feels disempowered. Similarly, when our opinion is dismissed. The ego-sleight is noted by those ever-vigilant beasts that snap into action and assassinate the offender’s character by turning him/her into a persona non grata, and there we are, in the blink of an eye, guilty of sinat chinam. By putting the offender down, the ego recovers its secure and superior position (at least in its own mind).

It becomes clear that behind all the brouhaha of unbridled machloket and sinat chinam, quietly, unnoticed, there is a gremlin in the works. And that gremlin is responsible for using all means at its disposal to defend us from shame, an aversive state herein defined as, “The discomfort produced when the ego feels diminished or deflated.”

Until we get a hold on how shame circulates through our psyche we don’t have a chance of eradicating sinat chinam. The author has written an entire book on this subject.[xiii] But for now we are putting shame aside and focusing, instead, on two stopgap practices that will help keep machloket from descending into milchama. True, they only address the symptoms and not the deeper cause, but symptomatic relief is still useful.

Practice 1 –A Commitment To Find Something True, Redeemable Or Even Admirable In Your Disputant

In machloket there is basic respect for the humanity of one’s opponent. You disagree on the matters under dispute but acknowledge that there are values that you share and matters that you agree upon. In the descent from machloket to milchama perceptions narrow and flatten. In milchama one views the other through a lens of black and white, which reduces them to a caricature that is 100% bad. The milchama perception lacks nuance and complexity.

In searching for something redeemable there are basically three options:

Practice 2 – The Practice of the Baal Shem Tov (as Rendered by the Komarna Rebbe) to Pray For the Enemy’s Teshuva and Spiritual Awakening

This is a profound practice with mystical underpinnings. The author has published a book on this teaching as presented by the Baal Shem Tov through his spiritual emissary, the Komarna Rebbe, R. YYYY Safrin.[xiv] Before presenting this practice I want to emphasize that we are not praying for our enemy to live long and prosper. We are praying for their teshuva which requires genuine remorse for their misdeeds and an appeasing of those who they’ve have harmed and a full payment of their karmic dues. In the most extreme cases, like in the Talmudic tale of Eliezer ben Dordai, teshuva for a lifetime of wanton sin can spark the penitent’s immediate demise. For now, I am speaking about Jewish enemies. The Komarna Rebbe extends the practice, but that is for another time. The teaching in brief…

For the purposes of this practice an enemy is anyone or anything that disturbs your peace. There are beloved enemies (like, perhaps, one’s teenager) and there are mortal enemies (like, a military combatant) and all points in between.

The teaching is that an enemy is always an upside-down soulmate. In the primordial shattering of vessels, HaShem’s instigating vision of reality splintered, fell and discombobulated. The sparks of all the elements of that founding vision got mixed up with each other, including the soul-stuff that would become each one of us. Consequently, there are slivers of our souls carried by others and slivers of their souls carried by us. Souls that are intermingled in this way are, literally, soulmates. An enemy is a soulmate of this sort.

An enemy holds an alienated spark connected to our soul that was so severely disfigured in the primordial breaking of vessels that we no longer recognize it as a piece of our very own self. This disowned sliver of fallen light lacks vision and emotional intelligence. Yet on a primal level it has chosen us as its opponent because it is trying, in its deluded way, to connect back to its root, which really is us.

Just like in right-side-up soulmates there is chemistry, so is that so, in up-side-down soulmates (i.e., enemies) as well. Thus, says the Komarna, the host of our alienated spark has fixated on us as its antagonist because, the spark it’s carrying needs us to pray for its redemption and that prayer will benefit the host as well.

Consequently, this practice as presented by the Komarna, is to pray for our enemy’s teshuva and spiritual awakening just like we pray for our own. The Komarna explains that this is a win all around.

A Peace Prayer and War Cry

(to be said with its parentheticals)

Let it be that every Jew (no matter where they stand or what they face) may they see the light (ie, Your light). And may they integrate that light so deeply into their being (into their heart, bones, cells and spaces, thought, speech and deed, that they (and we altogether) become the light, (ie the light unto the nations that is our truth and our destiny). And may we shine that light out into the world with a strength and a radiance and a glory that all the nations of the world, including our enemies among them, should see the light i.e. HaShem’s light as it shines through the Jewish people, their hearts should open, their lives should. they should repent, choose good and be redeemed.

[i] R. Tsadok, Pri Tsadik, RH 9; TB Brochot 6a] (כמ”ש מד”ת נשא כט)// מקיים כל המצות כמו שאמרו (מדרש רבה ריש פרשת

[ii] TB Brochot 6a.

[iii] I Chron. 17:21.

[iv] ספר רסיסי לילה – אות מח

[v] Lev. 19:18.

[vi] Biblical period

Second Temple and Roman period

[vii]ר’ אליעזר צבי סאפרין, אור עינים, אות ע’ – עם הארץ ; (Ramak, Pardes Rimonim 24:8 (חיתו שדי).

[viii] Eicha 1:9.

[ix] Tanya, chapter 27.

[x] Also some individuals only integrate from opposition. That excitement and concrete focus brings all their pieces together in their “noble” fight against whatever has become their nemesis.

[xi] R. Naftali Tsvi Berlin, HaEmek Davar, Intro to Bereshit.

[xii] Shmot 29:18; Bmidbar 25:8 ריח ניחוח. נחת רוח לפני, שאמרתי ונעשה רצוני:

[xiii] Dark Matters of the Soul—The Kabbalah of Shame.

[xiv] The book is called, “You Are What You Hate—A Spiritually Productive Approach to Enemies.”