This is a teaching about prayer as conveyed by the Komarna Rebbe (R. Yitzchak Eisik Safrin, 1806 – 1874). It is only tangentially related to Purim, though it does appear in his commentary on Megillat Esther. Furthermore, since Purim is a most propitious time for prayer, it is an appropriate teaching for the occasion. But mostly, it is a subject I wanted to broach, and this concurrence of commentary and prayer focus provides an opportunity to do so.

This is a teaching about prayer as conveyed by the Komarna Rebbe (R. Yitzchak Eisik Safrin, 1806 – 1874). It is only tangentially related to Purim, though it does appear in his commentary on Megillat Esther. Furthermore, since Purim is a most propitious time for prayer, it is an appropriate teaching for the occasion. But mostly, it is a subject I wanted to broach, and this concurrence of commentary and prayer focus provides an opportunity to do so.

The focus of the Komarna’s teaching is this following passage from Megillat Esther.

So Haman came in. And the king said to him, “What shall be done to the man whom the king delights to honor?” Now Haman thought in his heart, ‘To whom would the king delight to honor more than to myself?’ And Haman answered the king, “For the man whom the king delights to honor, let the royal clothing be brought which the king wears, and the horse that the king rides upon, and the crown royal which is set upon his head.” [ME 6:7-8]

וַיָּבוֹא הָמָן וַיֹּאמֶר לוֹ הַמֶּלֶךְ מַה-לַעֲשֹוֹת בָּאִישׁ אֲשֶׁר הַמֶּלֶךְ חָפֵץ בִּיקָרוֹ וַיֹּאמֶר הָמָן בְּלִבּוֹ לְמִי יַחְפֹּץ הַמֶּלֶךְ לַעֲשֹוֹת יְקָר יוֹתֵר מִמֶּנִּי: וַיֹּאמֶר הָמָן אֶל-הַמֶּלֶךְ אִישׁ אֲשֶׁר הַמֶּלֶךְ חָפֵץ בִּיקָרוֹ: יָבִיאוּ לְבוּשׁ מַלְכוּת אֲשֶׁר לָבַשׁ-בּוֹ הַמֶּלֶךְ וְסוּס אֲשֶׁר רָכַב עָלָיו הַמֶּלֶךְ וַאֲשֶׁר נִתַּן כֶּתֶר מַלְכוּת בְּרֹאשׁוֹ:

The Komarna’s commentary on this passage is kabbalistic, which means that meaningful phrases can be pulled out of context and interpreted as a unit unto themselves, independent of the sentence or subject of the larger piece. In this case R. Safrin interprets the verse that is bolded above as a teaching about meditative prayer and Torah study. It’s a famous instruction by the Baal Shem Tov that has no obvious connection to Haman’s actual conversation with the king, at least on the level of pshat.

The Komarna comments briefly and succinctly (in these three and a half lines),[1] yet to translate this teaching and unpack its message takes pages of English words.

וְסוּס אֲשֶׁר רָכַב עָלָיו הַמֶּלֶךְ הוא סוד כלים וגוף חשמל הנעשה מאותיות התורה אשר למד בעוה”ז ומבואר בתיקונים [תיקון ה כ: ועוד], ובדברי האר”י [שער היחודים ריש פ”כ] כד מפיק בר נש אתוון [-כשמוציא מאדם מפיו אותיות], הנקראים ‘סוסים’ רוכבין עליהם ‘שכינה נשמות מלאכים’ כפי לשון האריז”ל [שם] שהם סוד ‘עולמות נשמות אלקות’ בלשון הבעל שם טוב [אגרת הבעש”ט, בסו”ס בן פורת יוסף].

A literal translation of the Komarna’s comment: This is the secret of vessels and a radiant body created by the letters of Torah that one learns in this world, as explained by the Tikunei Zohar. According to the Ari: when one speaks letters aloud, they are called horses and the “Shekhina, Souls and Angels” can ride upon them, so says the Ari. This is the secret of “Worlds, Souls, Divinity” in the language of the Baal Shem Tov.

An elaborated translation of the Komarna’s comment:

A horse that the king rides upon: When a person prays or recites Torah, the spoken letters create keylim, meaning, “an expanded capacity to receive” the gift of additional light that the letters carry. This newly released consciousness transmitted by the letters enlightens a person’s body as well as their soul. Its cleansing nature dissolves something of the body’s opacity, eventually producing a guf chashmal, an enlightened body whose instinctive and reflexive response to the world is always in line with HaShem’s will, spiritual law, and Torah. And so, says the Komarna, these letters, like horses, introduce motion, strength, and carriage into the system. They can be harnessed and ridden.

The Komarna brings two paradigms to describe this phenomenon, one from the Ari and one from the Baal Shem Tov. Their language is similar, but different. Their respective terminologies highlight different layers of reality that become the focus of their respective inner work. The Komarna has many teachings that reconcile these two models. I am going to summarize them both but dwell primarily on the Baal Shem Tov’s version for it speaks more deeply to me as an instruction for meditative prayer. These two models could be characterized as ohr yashar (straight, descending light) and ohr chozer (returning, teshuva light). The Ari’s “Shekhina, neshamot, melachim” sequence define the stepwise descent of prayer and providence as we’ll see. And the Baal Shem Tov’s “olamot, neshamot, Elokut,” define the ascension of striving and study from below to above.

Beginning with the Ari: The Shekhina is the sum total of soul stuff in creation—human, animal, plant, and mineral—nothing exists except that HaShem wills it to be so. And that will breathes all things into existence and serves as their vital soul. In this sense the Shekhina functions as a kind of gestalt on the inner planes, a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts. And these parts (both living and inert) are, at one and the same time, her children and, yet equally, pieces of her very own self. Just as a child is both an independent other, and a literal piece of its parents in the sense that it carries the genetic stuff of its parents in every cell of its body.

The Shekhina thus shares our ups and downs, our joys and travails because our experiences are Hers as well. And so Her primary mission is to help us out—to guide us along the most efficient and least painful route to our destiny. And we, for our part, tune in to that flow of direction (and longing) by deepening our relationship to our own inner soul spark, which is rooted in the Shekhina and becomes the channel for receiving her messages. The greater the overlap between our personality’s field of awareness and its soul layer, the more we benefit from the Shekhina’s still small voice.

The neshama then translates the Shekhina’s message into thought, speech, prayers, and deeds that affect our own life and radiate their influence out to the world. Rambam defines angel as “the means by which a force exerts itself at a distance.” There are angels on the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual planes. The repercussions of our thoughts, words, prayers and deeds (triggered by the Shekhina’s vision) translated into practical action by the neshama, are the angelic horses that spread the Shekhina’s influence far and wide. So teaches the Ari .

Perhaps the Baal Shem Tov’s most famous teaching concerns the instruction he received in a soul ascension one Rosh Hashana eve. This excerpt from the full record of his experience is what concerns us here.

I received three potent practices and three Holy Names, easy to learn and explain. My mind settled for I thought that possibly, by means of these, men of my nature will be able to achieve levels similar to mine. But I was not given permission all my life to reveal this…. But this I may inform you and may G-d help you: your way should ever be in the presence of G-d and [this awareness] should never leave your consciousness in the time of your prayer and study. Every word of your lips is a unification: for in every letter there are Worlds, Souls, and Divinity, and they ascend and connect and unify with each other, and afterward the letters connect and unify to become a word, and [then] unify in true unification in Divinity. Include your soul with them in each and every state. And all the Worlds unify as one and ascend to produce an infinitely great joy and pleasure, as you can understand from the joy of groom and bride in miniature and physicality, how much more so in such an exalted level as this.

The Baal Shem’s Tov’s model of empowered prayer is a yichud of olamot, neshamot Elokut (worlds, souls, Divinity). It is a living practice that propels the practitioner into a multi-dimensional devekut. There are numerous teachings about how to fulfill this mysterious directive, to unite worlds, souls and Divinity (עולמות, נשמות, אלהות) through sacred speech (ie., prayer and Torah study). The teaching that follows is but one option.

The Zohar brings concrete images to convey ethereal truths. It portrays the spiritual realms as worlds stacked one atop the other, each with a floor and a ceiling of sorts.[2] And the only way to move up and down through the worlds is to find the central chute (like an elevator shaft) that passes through the center of each world and allows passage between them.

But it is not a simple task to find the center of a world. It requires a mastery of the paradox at the heart of that world—the right balance of truths and counter truths (the tikkun hamitkala) that marks the trap door, that opens into the mysterious central shaft.

This entire unification happens within a meditative state that is active, alert, receptive and expectant. So the first step is to drop into a meditative poise. Take three deep inhales and exhales, and then do whatever you normally do to enter the stillness where breath slows and thoughts quiet.

In this version of the Baal Shem Tov’s yichud, “Divinity” is the sacred text—the word of G-d—whether as the perfectly transparent prophesy of Moshe, or the cloudier revelations of the prophets or the inspired intuition (ruach hakodesh) of the Biblical Writings and prayer liturgy or even the lesser transmissions of teachers and plain folk sharing their life-truths. Each category has a different level of authority, to be sure. But for one with eyes to see, HaShem speaks through them all, for “Hashem’s seal is truth.”[3] Nevertheless, in this discussion, we are focusing upon prayer liturgy and Torah study (including Torah sh’b’al peh).

The practice begins by speaking (or even whispering) its words slowly, carefully, with a pause, for contemplation, after every one, two or three words. It helps to keep eyes closed as much as possible, and to open them (perhaps only one of them) just enough to scan the next word or phrase. This makes it easier to stay in the penimiut of things.

The “pause for contemplation” brings us to the service of ,“Worlds” which (in this interpretation) refers to sensory reality. Meaning that each word or phrase asserts a fact, describes a circumstance, presents a metaphor, awakens a desire, or conjures a possibility that happens in the external world. The practice, at the level of worlds, is to verify those scenarios by allowing oneself to experience each word’s unique flavor of consciousness by entering its reality for a brief moment.

Then comes “Neshamot (souls)” where one offers these words back up to HaShem as prayers or insights. The liturgy—invested with the heart and soul of Jews for millennia—has loft. Its power of uplift is tangible. Its words pierce the firmaments and whoosh up to their root via the central shaft, and bring the soul that released them along with. This ascent of word and neshama produces a devekut that is of great delight to the soul—a devekut of meaning and beyond meaning—a devekut ideally, ultimately, of pure lishmah.

PS: If you don’t relate to the words you encounter in prayer or study, then (in the pause) take a moment and try to reframe them in a way that does feel true. Prayer is called avodah sh’b’lev (service of the heart), so it is important that one’s heart and prayer be aligned. If you don’t find an interpretation that you are comfortable with, stay with the yichud, and afterwards, ask around. Ask friends and teachers what they think about when they say these words. Don’t stop until you’ve found a satisfying answer.

And so, here again, the letters become the horsepower that transports the soul into higher worlds producing a yichud of heaven and earth, that is, by some counts, the point of it all (if the Baal Shem Tov’s vision be our guide).

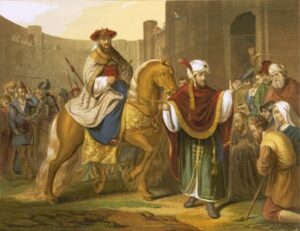

We saw that when Ahashveros asked Haman how to reward someone whom the king sought to honor, Haman assumed that he was the intended beneficiary and listed the honors that he would like to receive. One of his entries was to be led in procession riding a horse upon which the king had previously ridden. We know how this plays out in the actual story, the reversal, where Mordecai actually rides the horse and Haman parades him through the town.

The Komarna simply views this scenario from a higher plane, Ma’ase Merkava (the Divine Chariot). From that perspective his commentary really does fit with the pshat, for the Talmud informs us that the King of kings actually does (or did) “ride” upon the avot who, like spirited horses, spread the truth of ethical monotheism out to the world:

Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, ran before me like horses [spreading My name and My truths out to the world]. You will be amazed at their great and goodly reward. [TB San 96a]

We depend upon the merits and build upon the precedents of these noble “stallions”. We, too, like Mordecai, ride “horses” upon which the King has previously ridden. We ride them and HaShem rides us. The chariot still needs horses. The mission continues via the practices promoted by the Ari and Baal Shem Tov that serve as modern day horses upon which the King of kings rides and upon which His nation, Israel, builds.

On Purim—our day of bonefelt joy—we read the Megilla…twice. May the lights and repercussions of its holy words touch our souls and spread through world producing yichudim along with their “infinitely great joy and pleasure that surpasses all earthly delights,” עד דלא ידע [4].

פורים שמח

EAT, DRINK, AND BE HOLY

———————

[1] There is an illuminated edition of Ketem Ofir, the Komarna’s commentary on Megillat Esther, that includes punctuation, translation, footnotes and a slightly elaborated presentation of the original text. This Biur Meshulav, composed by his grandson, Matisyahu Safrin, is the version displayed above.

[2] Zohar, Parasht Vayakhel.

[3]TB Shabbat 55a.

[4] The Baal Shem Tov quote above, slightly amended.

1 Megillat Esther 3:9-14.

2 Megillat Esther 8:8

3 Esther Rabba, Prologue, 10.

4 Tiferet Tsion on Esther Rabba, Prologue 10.

5 Midrash Esther Rabba includes twelve introductions to the Megilla. It is the nature of these introductions that each rabbi presents what he feels is the overarching theme of the Purim tale.

6 R. Isaac Luria (Ari), Arba Meot Shekel Kesef, at the end (as quoted by R. Tsadok Hakohen, Tsidkat HaTsadik, #40).

6 TB Shabbat 156a.

8 TB Shabbat 156a.

9 R. Eliyahu Dessler, Michtav M’Eliyahu, vol. 4, p. 98 – 108).

10 When the Talmud asserts that “Fate does rule our livesיש מזל) (לישראל” it refers to this higher mazal.

11 Ibid.

12 “When the Talmud asserts that “Fate does not have power over our lives (אין מזל לישראל)” it refers to this lower mazal.

13 TB Moed Katan 28a.

14 TB Yevamot 50a; Nidda 70b; TB MK 28a; TB Brachot 31b; Pesikta Rabbatai 43:7; Bible stories of the patriarchs and matriarchs and Chana, M. Shabbat 2:6.

15 TB Shabbat 156a.

16 Regarding Achashverosh’s teshuva see Yaarot Devash as brought by Me’am Lo’ez on Esther 7:5 (and 7:10).

17 R. YYY Safron (The Komarna Rebbe) in Ketam Ofir on Esther 1:1; The Shela, Notes to Sefer Bereshit, Parshat vayetze.

18 Megilla 8:8-13;

19 Rambam, Hilchot Teshuva 3:1.