This Tu B’Shvat teaching is dedicated to the complete and speedy recovery of Shoshana bat Sarah and was sponsored by some of her friends.

Tu B’Shvat is the New Year’s day for fruit trees but it is important to note that this is not their day of judgment—that occurs months later in Sivan, on the holiday of Shavuot. The Mishna makes a distinction between these two types of days and lists four examples of each. The four New Year’s days are:

Tu B’Shvat is the New Year’s day for fruit trees but it is important to note that this is not their day of judgment—that occurs months later in Sivan, on the holiday of Shavuot. The Mishna makes a distinction between these two types of days and lists four examples of each. The four New Year’s days are:

1st of Nissan – which starts a new year when reckoning the length of a king’s reign.

1st of Elul – which starts a new year for the tithing of animals (meaning that 10% of the livestock born in the previous year must be formally designated as gifts for the kohanim before this date).

1st of Tishrei (which is also Rosh HaShana) – which starts a new year for the counting of history as well as the tithing of grains and vegetables (and also for counting Sabbatical years).

15th of Shvat – which starts a new year for the tithing of fruits.

In contrast, the four judgment days are:

Pesach (15th of Nissan) – when Heaven decrees how much grain will be reaped in the coming year.

Shavuot (7th of Sivan) – when Heaven decrees how much fruit will be gathered in the coming year.

Rosh HaShana (1st of Tishrei) – when the spiritual (and by extension, material) resources that will be available to each creature are determined for the coming year.

Sukkot (15th of Tishrei) – when Heaven decrees how much rain will fall in the coming year.

There is one point of overlap between these two lists, and that is Rosh HaShana (the 1st of Tishrei) which is both a New Year’s and a judgment day.

We are all familiar with these judgment days—though we don’t usually think of them as such—for they are better known as our most distinguished holy days and, consequently, we observe them with great fanfare, as specified by the Torah. We refrain from melacha (creative work) and perform special rituals that help us absorb the spiritual gifts available on those days. Yet, our prayers and mitzvot apparently serve another purpose as well—they generate a pile of merits that will, hopefully, tip the scales toward a favorable verdict in the blessings that are allocated on those holy judgment days.

New Year’s days are different. Besides Rosh HaShana, they can pass unnoticed for without the Temple, there are no Torah obligations associated with them and, for city folk, especially outside the land of Israel, there is no practical observance that applies. So how do we mark these “minor” New Year’s days.

One clue is that the Hebrew word for New in the term New Year, actually, literally, means head (rosh). The idea is that according to kabbala, the beginning (or rosh) of something actually contains all the lights that are going to unfold in whatever it is the rosh of. Consequently, Jewish practice instructs us to give special attention to those first moments of each new cycle of time and fill them with prayer and holy thoughts. At the instant of wakening (the rosh of the day) we recite a prayer of gratitude; on the New Moon we sing Psalms of Praise (i.e., Hallel) along with special prayers; and on the rosh of the year we spend the entire day in prayer and celebration. Everything that occurs during that inaugural period (deeds, thoughts, prayers, emotions) impact the head of that cycle. And since the head defines and delimits future possibilities, anything that affects the head, affects all that will unfold in that cycle, even if its only contact with that cycle was in its first moment of formation.

Tu B’Shvat is the rosh of the fruit tree’s new year. All creatures have biorhythms. Plants go dormant in the cold winter damp. Bared of foliage trees look dead; they give no sign of viable life. Then in spring a growth phase begins; they bud and flower and bear their fruit. On Tu b’Shvat the sap starts to rise and signals the flora to prepare for rebirth. It is the turning point when the plant kingdom shifts from death toward life.

As above, so below. As without, so within. The human being is a macrocosm that contains something of all the different layers of creation within itself. That’s one interpretation of what it means to be created “in the image of G-d.” And so, says kabbala, we all have a:

Mineral layer that includes the physical materials, the “dust and water” out of which we are formed;

Plant layer that includes all the vegetative functions that our body constantly performs: cell divisions, circulation, respiration, metabolism, etc.;

Animal layer that includes all the primitive thoughts and emotions, fight or flight responses, locomotion, pleasure principle, reproductive drives, etc.;

Human layer that includes our speech and conceptual thoughts, complex emotions, visions and aspirations.

And it is the vegetable layer that oversees our physical health. Its autonomic activity heals wounds, balances hormones, neutralizes toxins, metabolizes food, eliminates intruders, etc. (In contrast, the animal layer manages our emotional health, which is why efforts toward self-improvement must enlist its support if they are to produce enduring change.)

Consequently, Tu B’Shvat marks the point in our own biorhythms when one cycle of health completes itself and a new cycle begins. Tu B’Shvat is an opportunity to regroup, correct imbalances, and begin a new phase of health and healing—to boost the body’s efficiency on the vegetable layer.

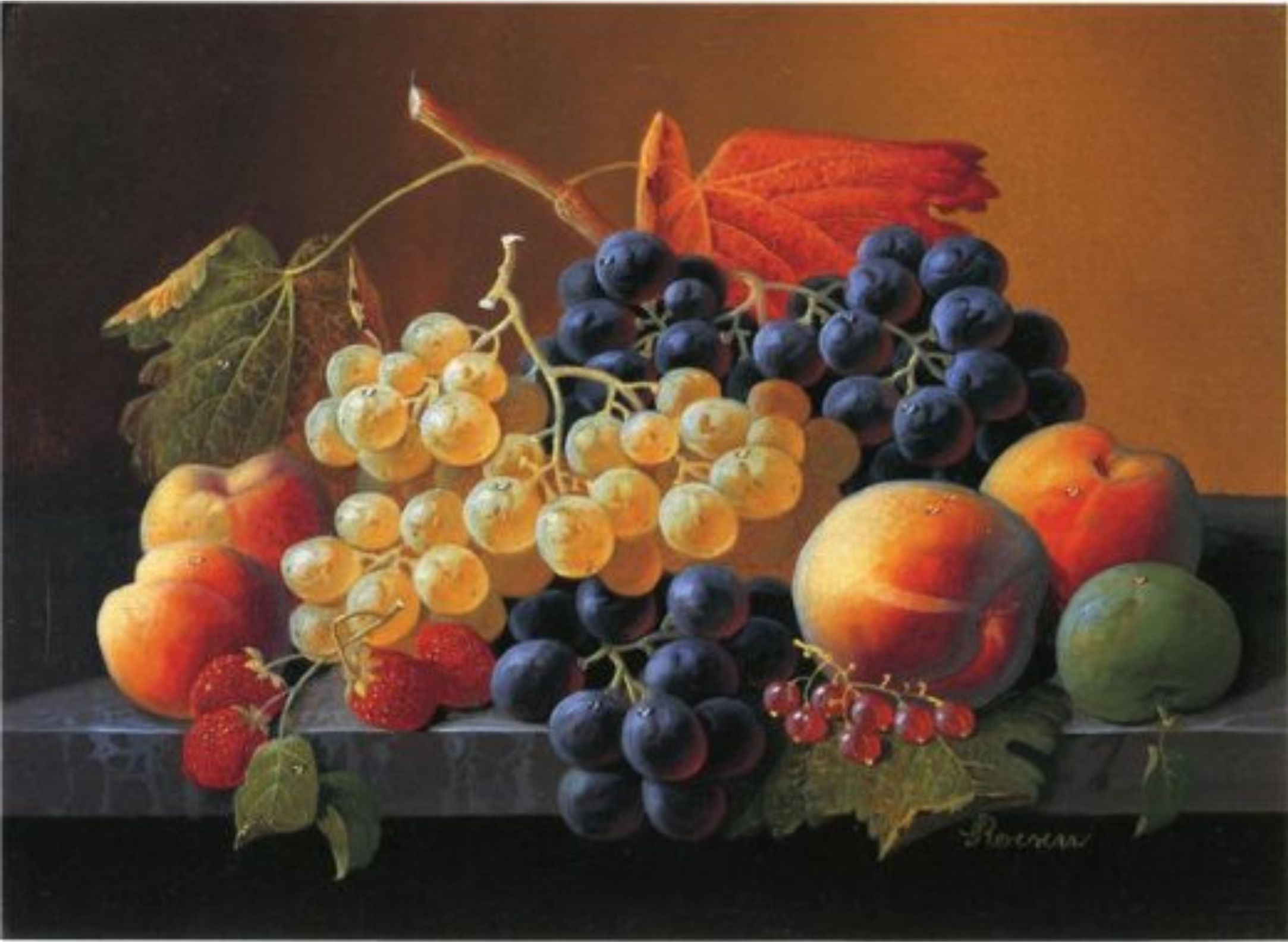

What is the practice? How do we make the best use of the energies available on this New Year’s day for fruit trees? The tradition is simple: eat fruits of all sorts; admire the shape, color, taste and uniqueness of each one; and say blessings with deep intention.

This is actually a powerful practice; it conveys a deep secret about how to exert positive influence over the body’s vegetable layer that normally operates beyond conscious control and which oversees our physical wellbeing.

1) By surrounding ourselves with fruit of every sort, the successful harvest of last year’s cycle, we impress the picture of robust health onto the plant layer of ourselves using symbols that are meaningful to it. The form and color of each fruit is an icon that triggers associations in the plant layer of soul. These subliminal suggestions of health and success penetrate the unconscious and leave transformation in their wake. Each fruit expresses a unique way of turning raw materials into something that is beautiful, healthy and life-nurturing. Admire the fruit. Notice its shape, color, taste and beauty.

2) Pray. Say your brachot with special intention. Create your own blessing for yourself and others that expresses the particular beauty of each fruit as an affirmation, for example, “Your cheeks should be as rosy and your Torah as sweet as this crisp and rosy apple.”

3) Eat with remembrance of G‑d. Meditate on the Creator of the fruit as you bite, chew and swallow it.

I want to bless us that as individuals, as members of the community of Israel and the larger world community that we should, through our Tu B’Shvat celebration, draw the special lights of this time into the depths of our souls, and of the world and of every creature in it, bringing light and trust and healing there. And in so doing may we contribute, in our small way, to the six millennial process of tikun olam. May all that we do be pleasing in HaShem’s eyes.