Blessed Be the Makom…Blessed Be the Giver of Torah…

Pesach 5777 / 2017

Sarah Yehudit Schneider

Blessed be the Makom (Place). Blessed be He. Blessed be the one who gave Torah to His people, Israel. Blessed be He. The Torah addresses four children. The wise one, the bad one, the simple one, and the one who doesn’t know to ask.

בָּרוּךְ הַמָּקוֹם, בָּרוּךְ הוּא, בָּרוּךְ שֶׁנָּתַן תּוֹרָה לְעַמּוֹ יִשְׂרָאֵל, בָּרוּךְ הוּא. כְּנֶגֶד אַרְבָּעָה בָנִים דִּבְּרָה תוֹרָה: אֶחָד חָכָם. וְאֶחָד רָשָׁע. וְאֶחָד תָּם. וְאֶחָד שֶׁאֵינוֹ יוֹדֵעַ לִשְׁאוֹל

Before launching into the Exodus story the rabbis praise G-d and then specify their audience. Yet the terms used to signify Hashem in this brief tribute allude to the two modes of providence HaShem employs to assure that creation achieves its success.

Blessed be the Place

The first is HaMakom (המקום)—literally, The Place—the circumscribed Space-of-Creation. HaMakom refers to the womblike vacuum produced by the cosmic tsimtsum that hosts the unfolding of creation from Bereshit till the end of time. Generally we think of environment as secondary to the creatures that live within it. Yet R. Shlomo Elyashiv (Leshem) teaches that the space (or Place) of a world actually derives from a higher root than the fawn and flora (including ourselves) that reside within it.[1]

HaMakom includes our earthly surroundings, as well as the laws of nature (both physical and metaphysical) that together comprise our reality. Yet what dictates the features of its patchwork of ecosystems from barren desert to lush rainforest, frigid arctic to sweltering equator, urban slum to country farm? “HaShem looked into the Torah and created the world.”[2] This vibrant Makom is nothing but the embodiment of HaShem’s will-for-creation and thus serves as a primary agent of Divine Providence. It exerts constant pressure on its inhabitants to evolve in particular ways by requiring certain innovations and hindering others.

HaMakom has many layers to it, from coarse to subtle, material to spiritual. Our quality of life depends upon our alignment with and mastery of its complex reality. What works and what doesn’t…short-term and long-term? Which choices bring joy and profit and which produce the opposite? All this is controlled by HaMakom and our (successful, or not) adaptation to it. Avraham and Sarah were masters. They derived the entire Torah—with its 613 revelations of Divine will—by observing the world, extracting its providential messages and adjusting their lives accordingly.[3]

“HaShem is to creation as the soul is to the body.”[4] Just as the soul fills both conscious and autonomic functions, so is this true for HaShem. Our body’s autonomic functions include, for example, circulating the blood or taking a breath. We can learn to consciously alter our blood pressure by directing our attention there but, for the most part, our automatic pilot does just fine. HaShem’s autonomic mode is HaMakom—Nature. Its built-in reinforcements (positive and negative) sculpt the unfolding of creation. And for humans, who engage with its psycho-spiritual layers, the Makom’s ingrained “rewards and punishments” train us to become connoisseurs of pleasure—to prefer manna to quail, enduring joys to fleeting ones—and to chart a life path that maximizes the former (not from self-denial, but because we see that it’s the most profitable option).

Blessed Be the One Who Gave Torah to Israel

The ten statements of “Let there be…” that brought forth the entirety of creation[5] correspond, one to one, with the Ten Commandments, which present the entire fabric of Jewish theology. God expresses Himself through each, though in the first He employs the language of symbol (i.e. the objects of creation and natural law), while in the latter He uses words and explicit instructions.[6] Each, in its own alphabet, presents the full content of Divinity’s communication with creation. There can be no contradiction between them, for both derive from the same One that conceived creation, birthed it into being, and then revealed His will for that creation at Sinai.

The Torah is a compendium of pointers from the Creator of the Makom Itself, providing a bounty of information about the nature of reality and how to make the best of it. We Israelites are an ancient people that have survived millennia…and thrived…despite exiles, inquisitions, pogroms, and holocausts. Our secret is the Torah that reveals the metaphysical laws governing our world and aligns us with even the most subtle layers of reality (aka, HaMakom). We don’t have to derive this wisdom on our own, as did Avraham and Sarah. The Torah is a textbook of spiritual physics with 613 practices that adapt its practitioners to the ever-changing demands of reality and thereby assures their success.

The Torah addresses four [types of] children.

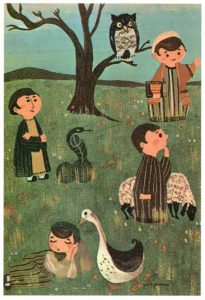

It is clear that the rabbis consider both of these channels of providence essential to a balanced and fully integrated Jewish life, as indicated by the questions and answers that follow. Each of the four children highlighted below have their strengths and weaknesses around these two modes of providence: HaMakom and HaTorah.

The wise child asks…

“What are the testimonies, the statutes and the laws which HaShem, our G-d, has commanded you?” You, in turn, shall instruct him in the laws of Passover: one must not eat any dessert after the Pascal-lamb.מָה הָעֵדוֹת וְהַחֻקִּים וְהַמִּשְׁפָּטִים אֲשֶׁר צִוָּה יְי אֱ-לֹהֵינוּ אֶתְכֶם [דברים ו:כ]. וְאַף אַתָּה אֱמוֹר לוֹ כְּהִלְכוֹת הַפֶּסַח אֵין מַפְטִירִין אַחַר הַפֶּסַח אֲפִיקוֹמָן

The Wise Son (חכם) asks a sophisticated question that displays his grasp of the nuanced distinctions between the various mitzvot. Yet those details (although impressive) were largely unnecessary, so the rabbis’ response includes a hint of rebuke as indicated by the word, af (אף). The chakham is too much in his head. The rabbis instruct him to develop his taste buds for holy pleasure, called simcha shel mitzvah (the deep satisfaction that comes from doing good). It’s not about what you know in your head, it’s about what you integrate into your heart. It’s about genuinely tasting the sweetness of the Pesach-Afikoman (which for us is the last portion of matzah) that even if the Torah did not instruct us so, we would naturally savor its sweetness and call it dessert. The chakham is strong in Torah but his pleasure-buds are still “uneducated.”

The ”Bad” child asks…

“What is this service to you?” [Ex 12:26] “To you,” but not to him! By excluding himself from the community he denies what is inviolate. You, therefore, blunt his teeth and say: “It is because of this that HaShem did for me when I left Egypt” [Ex 13:8]; for me – but not for him! If he had been there, he would not have been redeemed!

רָשָׁע מָה הוּא אוֹמֵר. מָה הָעֲבוֹדָה הַזֹּאת לָכֶם [שמות יב:כו]. לָכֶם וְלֹא לוֹ. וּלְפִי שֶׁהוֹצִיא אֶת עַצְמוֹ מִן הַכְּלָל כָּפַר בְּעִקָּר. וְאַף אַתָּה הַקְהֵה אֶת שִׁנָּיו וֶאֱמוֹר לוֹ. בַּעֲבוּר זֶה עָשָׂה יְי לִי בְּצֵאתִי מִמִּצְרָיִם [שמות יג:ח]. לִי וְלֹא לוֹ. אִלּוּ הָיָה שָׁם לֹא הָיָה נִגְאָל

The “Bad” Child (רשע) is actually demanding authenticity. He can’t just follow by rote and refuses to participate in a mindless routine. The Rasha is asking a real (but threatening) question: “Don’t give me theology. I want to know what this mitzvah business does for YOU, because it does nothing for me. I don’t connect. It’s just a bunch of constrictions that cramp my style. Perhaps you can open my eyes to a compelling benefit that will convince me to stick around.”

To “blunt his teeth” is to convey that questions are fine, but they must be founded upon a commitment to the mission (and the tribe). Before Sinai, you could leave the fold and renounce it forever. In Egypt, folks who lacked commitment stayed behind.

Now, because of what happened on that first seder eve—that we fused into a collective entity greater than the sum of its parts—because of that, you will never be left behind.[7] לא ידח ממנו נדח – Every Jew has a portion among the souls of Israel and cannot sever permanently from it. That cosmic fusion is what we celebrate tonight. Now, post-Sinai, like it or not, whatever choices you make—whether you veer from “the derekh” or stay firmly on it—either way, by the end, you will do your teshuva (like the rest of us) and find your way to the light. You are a member of the Jewish people, inheriting both the perks and the burdens of our noble lineage and chosen status.

The Rasha is weak in his alignment to both Torah and Makom, yet his passionate questioning and search for authenticity propels change and will, eventually, serve him well.

The Simple Child (Tam) Asks…

“What’s this?” And you shall answer: “With a strong hand HaShem took us out from Egypt, out from the house of slavery.” [Ex. 13:14]

תָּם מָה הוּא אוֹמֵר. מַה זֹּאת. וְאָמַרְתָּ אֵלָיו בְּחוֹזֶק יָד הוֹצִיאָנוּ יְי מִמִּצְרַיִם מִבֵּית עֲבָדִים

The Simple Child (תם) holds the place of simple faith which has, perhaps more than anything else, fostered our survival. The Tam knows beyond knowing, in the depths of his/her soul, that being a Jew is a priceless gift. And (unlike the Bad Child) whether s/he understands the whys and wherefores or not, s/he staunchly holds the faith. The problem is that s/he’s not so successful in transmitting that commitment to the next generation.

The Tam is tuned into HaMakom but lacks the Torah knowledge to inspire others.

Concerning the one-who-doesn’t-know-to-ask…

You must awaken [a question in] him, as it is says: “You shall tell your child on that day, ‘It is because of this that HaShem did for me when I left Egypt.’” [Ex. 13:8]

וְשֶׁאֵינוֹ יוֹדֵעַ לִשְׁאוֹל אַתְּ פְּתַח לוֹ. שֶׁנֶּאֱמַר, וְהִגַּדְתָּ לְבִנְךָ בַּיּוֹם הַהוּא לֵאמֹר בַּעֲבוּר זֶה עָשָׂה יְי לִי בְּצֵאתִי מִמִּצְרָיִם: [שמות יג:ח]

The One-Who-Doesn’t-Know-to-Ask is in such a state of devekut that there are no more questions: “It’s all good. G-d is one. Truth is obvious. There’s nothing more to say.” This child-without-a-query is positively aligned with both channels of providence (Torah and Makom) yet without a question, there is nothing to instigate growth. His exalted state is also a static state.

We come into the world to enlighten our ego-nature. It’s great to experience devekut but it can lead one to assume they are already enlightened when, really, the “high” of devekut has merely suppressed their inner skeptic, but not yet, fully transformed it. This child needs to make space for the voice of his inner malcontent (i.e., rasha) along with its irksome questions (as taught, concerning the Hagada’s opening invitation to the “hungry and needy,” in the Still Small Voice Passover Teaching from 2010 / 5770 based on the Baal Shem Tov).

Let it be that on this holy Pesach eve—the anniversary of our peoplehood—that we renew our commitment to the mission of shining the Makom’s holy truths out to the world, down through the layers of our being, and forward to the next generation.

A HAPPY AND KOSHER PESACH TO ALL!

[1] R. Shlomo Elyashiv (Leshem), Shearim v’Hakdamot, p35 (upper left); and many places.

[2] Zohar 2:161b.

[3] TB Yoma 28b.

[4] TB Brochot 10a. He said to him: What I meant to tell you is this: To whom did David refer in these five verses beginning with “Bless the Lord, O my soul”? He was alluding only to the Holy One, blessed be He, and to the soul. Just as the Holy One, blessed be He, fills the whole world, so the soul fills the body…

[5] Actually the phrase, “Let there be…” only appears nine times. The Talmud then counts the first verse of Genesis, “In the beginning…” as the tenth fiat (TB Megila 21b).

[6] God is beyond gender, containing both male and female elements as well as levels of oneness where even the duality of gender does not exist. The essential name of God, called the Tetragramaton, is androgynous. It contains two masculine letters (י, ו) and two feminine letters (ה, ה). Similarly, Genesis 1:27 describes the first human as “created in the image of G‑d…male and female.” Nevertheless the dilemma remains of which gendered pronoun to use when writing about G-d. The author has chosen to continue with the custom of “He” simply because changing this implies various ideological affiliations and associations that are not hers.

[7] R. Tsadok Hakohen, Pri Tsadik, Pesach 8.