Purim 2019 / 5779

Sarah Yehudit Schneider

Based on R. Y Safrin of Komara’s Commentary on Esther called Ketem Ofier (4:1 – 5:4) Mordecai charges Esther to go before the king, and plead for her people….[Esther warns that] “Anyone entering the king’s sanctum uninvited incurs death unless the king extends his golden scepter and grants them life.” Esther confides that she has not been called by the king for thirty days [implying that she’s likely to receive an invite soon] …Mordecai responds: …”Don’t think you can escape this decree in the king’s palace…Deliverance will come to the Jews from elsewhere and you and your father’s house will perish. Who knows whether it’s not for this very reason that you were crowned queen?” Esther replies: “Go and gather all the Jews present in Shushan and fast for me—neither eat nor drink for three days, night and day; I and my maidens will fast as well. And then I will go to the king, though it is against the law; and if I die, I die.” Mordecai … did according to all that Esther commanded him. [Esther 4:8-17][1]

Mordecai charges Esther to go before the king, and plead for her people….[Esther warns that] “Anyone entering the king’s sanctum uninvited incurs death unless the king extends his golden scepter and grants them life.” Esther confides that she has not been called by the king for thirty days [implying that she’s likely to receive an invite soon] …Mordecai responds: …”Don’t think you can escape this decree in the king’s palace…Deliverance will come to the Jews from elsewhere and you and your father’s house will perish. Who knows whether it’s not for this very reason that you were crowned queen?” Esther replies: “Go and gather all the Jews present in Shushan and fast for me—neither eat nor drink for three days, night and day; I and my maidens will fast as well. And then I will go to the king, though it is against the law; and if I die, I die.” Mordecai … did according to all that Esther commanded him. [Esther 4:8-17][1]

ענין ידוע ומפורסם לכל משכיל, שהשיחה בין מרדכי ואסתר הוא למטה, ורומז למעלה למעלה…שהיה ויכוח ביניהם על מה הוא הדרך הנכון לבטל את גזרת המן להשמיד את ישראל, ולבסוף הודה מרדכי לדברי אסתר…

Every learned person knows that this conversation between Mordecai and Esther, although it concerned worldly matters, it also encodes a debate about which kabbalistic strategy they should employ to annul Haman’s genocidal decree…In the end, Mordecai defers to Esther on all points. [Komarna Rebbe][2]

R. Safrin reads this dialogue between Esther and Mordecai as a coded debate about how to quash Haman’s murderous plan. They are communicating through the language of symbols. Mordecai proposes moderation [conveyed by his donning of sackcloth and stopping short of “the king’s gate”].[3] Esther vetoes that plan and suggests another [by sending her messenger, whose name is Hatach, a rearrangement of the letters of the holy name that Moshe used to invoke the lights that killed the Egyptians that were abusing Israelite slaves.].[4] Our best hope, she asserts, is to work on the inner planes and flood the kingdom with or chadash—producing an invisible downpour of holy light that will subvert evil and accelerate its demise. Mordecai agrees and directs Esther to perform yichudim—deep kabbalistic meditations— to accomplish the task [when he urges her to confront the “King”].[5] Esther objects because the people have not yet repented for indulging in the king’s traif banquet [by mentioning “30 days” she hints to the “30 tikunim of malchut” that still require teshuva].[6] Consequently, the holy lights released from yichudim are likely to harm them as well as Haman.

Esther suggests an alternative plan.[7] “Let all the people fast for three days, fusing into their higher-order unity called Kenesset Yisrael with all the grace and power that entails. Their fast will be the outer stimulus for an authentic atonement awakened within. And you, Mordecai, must join in this teshuva—by identifying a transgression of your own and repenting for real.[8] Only by sharing can you uplift them. And, since you insist on immediate action, our three-day fast will include Layl Seder overriding the mitzvah of matzah and maror. The message is blunt: if the people cease, the Torah has no point.[9] I will also fast, and spend those days in meditative prayer. And then I will visit the king uninvited, and if I die…I die.

In accepting this mission, Esther agreed to perform a kabbalistic ritual that had backfired on the most illustrious tsaddikim and chakhamim before her.[10] Her holy errand was to navigate through the PaRDeS, enter the [King of] King’s inner sanctum uninvited and subdue the forces of evil. Adam, Noach, Nadav and Avihu, the entire DorDeah and King Solomon had all attempted similar missions and failed. [Leshem, HDOH 2:4:20:4/5].

Esther needed a plan. How could she succeed when her predecessors had not. Mordecai and Esther each proposed a strategy, both of which were based on a kabbalistic paradigm called keter–malchut (keter being the highest of the ten sefirot and malchut being the lowest). The word keter (crown) only appears three times in the whole Tanakh and all three are in the Book of Esther and always in the phrase “keter–malchut” which hints to a powerful kabbalistic practice, called yichud.

Esther and Mordecai grappled with the same problem, employed the same paradigm yet arrived at different conclusions. To explain their divergence we must explore the mystery of yichud?

Our universe has a pulse and it originates at the highest echelon, with the Holy One’s vibration between ayin and ani—NoThing ((אין and I-Am (אנכי)[11] or, more concisely, ani (אני). When HaShem enters His ayin pole, there is nothing but G-d and creation dissolves into non-existence. When HaShem contracts back into His I-Center (אנכי) and assumes His persona, that we call, G-d (אלקים),[12] creation recovers and reengages with its Maker. In each instant, creation dissolves and reconstitutes, again and again.

This ani-ayin pulse pervades the universe and plays itself out on the human scale as well. We all vacillate between self-assertion and self-surrender sometimes in more and sometimes in less functional ways.

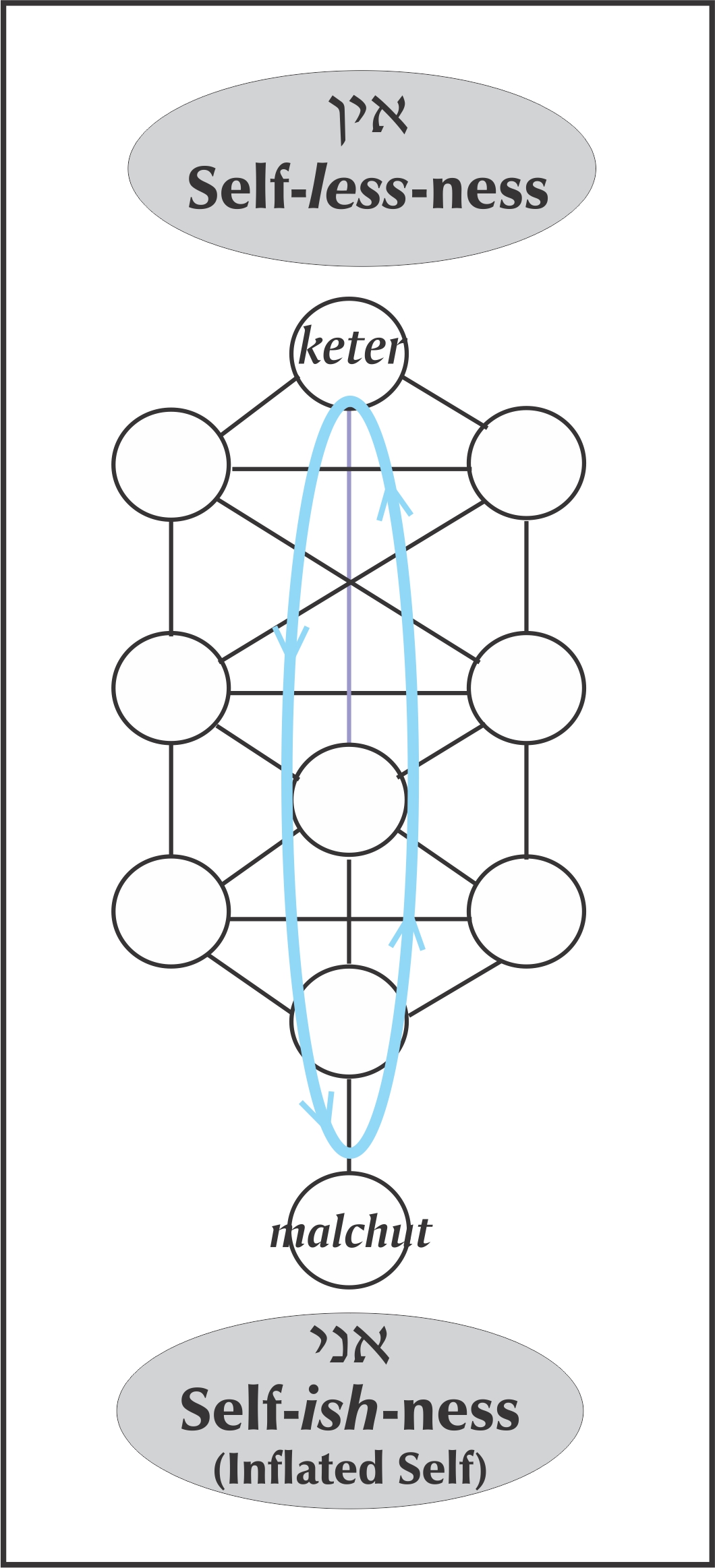

Kabbala maps these two polarities onto the sefirotic Tree of Life: Our selflessness (our ayin pole) associates with the sefira of Keter, which represents the most exalted (superconscious) level of soul.[13] Our self-ish-ness (or ani pole) associates with malchut the lowest sefira, farthest from the crown and sullied by its contact with the dross of shattered worlds, as kabbala interprets the verse from Proverbs: “Her feet stick down into death.” [Mishley 4:5] When reality collapsed, malchut (the lowest of the sefirot fell out of the realms of kedusha, into the shadowlands (called klipot) where death, delusion and impurity reign.

Kabbala maps these two polarities onto the sefirotic Tree of Life: Our selflessness (our ayin pole) associates with the sefira of Keter, which represents the most exalted (superconscious) level of soul.[13] Our self-ish-ness (or ani pole) associates with malchut the lowest sefira, farthest from the crown and sullied by its contact with the dross of shattered worlds, as kabbala interprets the verse from Proverbs: “Her feet stick down into death.” [Mishley 4:5] When reality collapsed, malchut (the lowest of the sefirot fell out of the realms of kedusha, into the shadowlands (called klipot) where death, delusion and impurity reign.

From this perspective a spiritual path starts in malchut and aims toward keter. Our work is to reduce ani (ego) and cultivate ayin (self-transcendence or, more concisely, NoSelf). This is how kabbala views the matter.

Yet this model is not as universal as it purports for (upon closer inspection) it reflects a particular I-center—the rabbinic I-center—that is (traditionally) male. Consequently, it conveys the masculine archetype’s experience of the ani—ayin polarity, where a toughened ego needs to be softened, dissolved and universalized.

A reminder that we are dealing with archetypes here, not people. Archetypes are pure tones, whereas people are complex and holographic. Kabbala calls these archetypes partzufim. They are the pure elements that mix and match to produce our messy real world with its multifaceted, rainbow reality. It’s called the Rectified World because of its holographic structure wherein every piece contains aspects of every other piece inside itself.[14] In the Rectified World every good contains a trace of evil and every evil a trace of good. Every man contains a shadow woman and every woman a shadow man. This feature of Interinclusion means that every person combines a spectrum of traits in varied proportions that produce his or her unique soul-print. And yet, it is still generally true that, men will tend toward the masculine archetype and women toward the feminine.

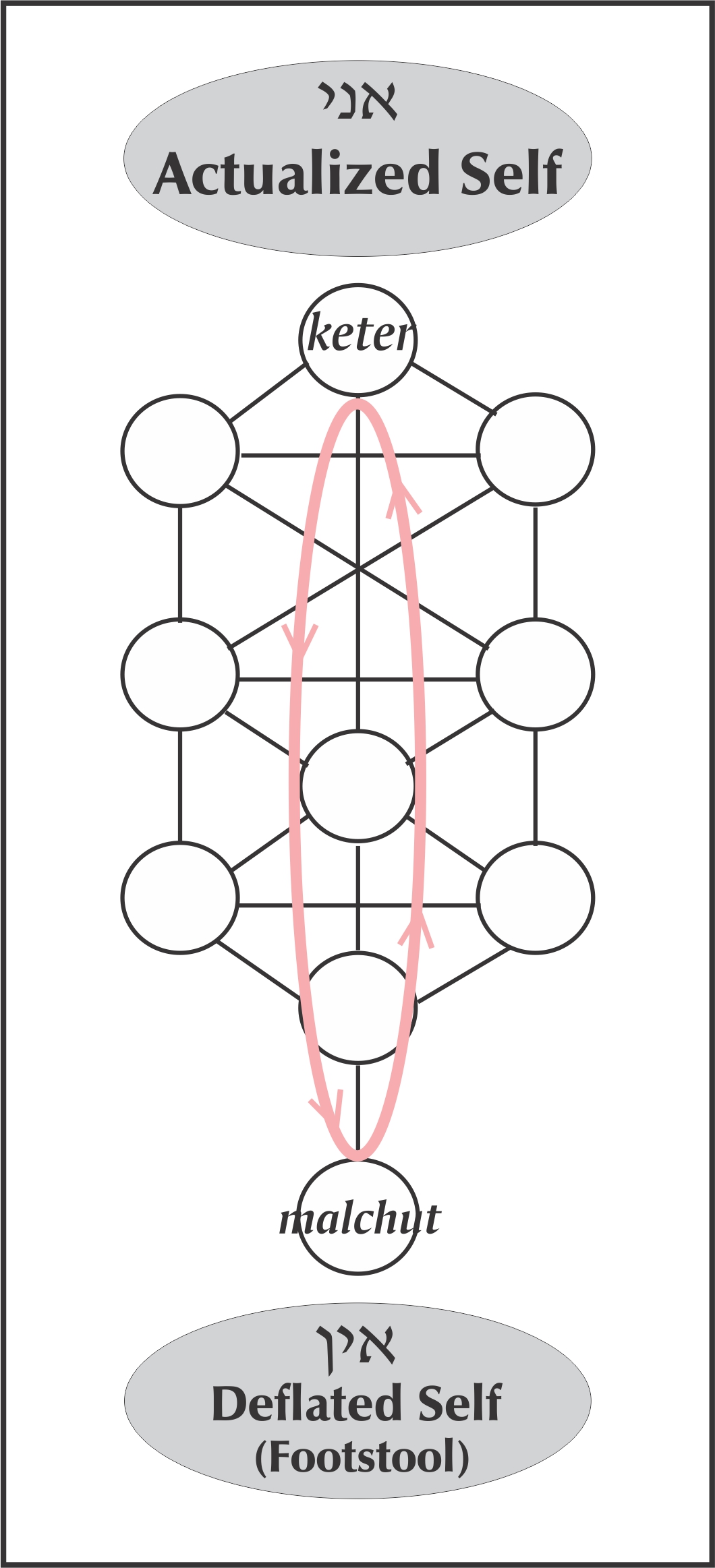

<And so, now, exploring the feminine archetype’s experience of the ani – ayin polarity—her path of tikun is actually the opposite of his. Kabbala ascribes moonlike properties to the Shekhina—God’s feminine expression—as malchut:

Just as the moon has no light of her own, only what she receives from the sun, so does the Shekhina have no light of her own, but what she receives from her mate, HKBH.

Consequently the Shekhina in malchut manifests as ayin—NoThing—for when she is there then, like the moon, she has no light of her own.[15] In malchut she is the footstool. Yet, says the Leshem She has another (hidden) side to Her, which is actually Her truest self and the polar opposite of Her moonlike dependence.[16] Secretly, the Shekhina is the crown; she is the wellsprings of bounty that births everything into existence. Whatever any mashpia (anywhere in the universe) has to give to its dependents, it draws it all from Her. The Shekhina manifests below (in malchut) as the utterly dependent NoThing, but secretly, the very charity she seeks from her benefactor (meaning HKBH), is nothing but what She, Herself, has supplied to that benefactor in Her keter mode. The Leshem brings a verse from Isaiah that expresses the Shekhina’s secret life.

I am the first [in keter] and I am the last [in malchut]…. [Isaiah 44:6]

The feminine’s teshuva journey is thus the polar opposite of her male counterpart. Whereas the masculine strives for ego-transcendence (the rectified ayin that is his keter)…the feminine cultivates holy selfhood (the rectified ani that is hers). In brief:

Rectified ayin is when the ego becomes perfectly transparent. It is the path of prophesy that requires its practitioners to face (and even embrace) the ego-deaths that dissolve the individualisms that inevitably personalize, and thereby alter, the transmission. This (masculine) path from ani to ayin is about learning to die. As Rabenu Bechaya teaches:

“You want eternal life?! Then you must die [in each breath], in order not to die.” Meaning that you must die to all that is subject to death and, in so doing, you will come to identify with the eternal component of your being that transcends death. [Rabenu Bechaya-Shaari teshuva 2:17, as explained by R. Dessler, Michtav M’Eliyahu 2:15.][17]

Rectified ani is the striving for authentic self. Our job is to actualize our full potential by negotiating all the contrary tugs arising from within and without, incorporating them in right measure, and all the while staying true to our self—a Self that is constantly changing, evolving, deepening and shedding old ways. Ani Tefila (I Am prayer).[18] This path of ani is about refining and aligning will so that our natural prayer and preference is to do what we’re designed to do (which is all that Hashem asks of us). The fruit of this labor is our fully actualized (and individuated) soul-spark that endures eternally as our “portion in the world to come.” This (feminine) path from ayin to ani is about learning to choose life (in the most profound sense of that word). It is no wonder that Chava (Eve) is called “אם כל חי” (mother of all life).[19]

Now let’s view Mordecai’s and Esther’s respective visions of yichud through this ani-ayin lens:

Mordecai’s plan (says R. Safrin) was for Esther, to “raise ani to ayin” which is the solitary (masculine) path of ego-death and yichud. The “tsaddik” ascends with his/her toolkit of kabbalistic formulae and clears out the channels so the lights begin to flow again. But (says the Leshem), on a national level, the only people who have succeeded in such a mission are those that were invited (nay, commanded) to do so by HaShem.[20] The others, who acted on their own (albeit, pure) initiative, crashed and burned. Esther was also not invited so it made no sense for her to follow a precedent of failure. Esther devised a different scheme, and Mordecai concurred. She would apply the feminine version of keter–malchut and hope for the best.

“To the Jews there was light and gladness, joy and honor” [Megilla 8:16].

Esther actually achieved what the four who entered PaRDeS (also without an invite) were trying to do.[25] Only R. Akiva survived that attempted yichud unschathed. But whereas he only managed to save his own skin,[26] Esther actually came out with the goods. There was no offence taken by her intrusion, rather she was invited to state her request. And at the end of her yichud, she actually did change history, redeem her people, and vanquish the scourge of Amalek in her day.

This crisis-solving dialogue between Esther and Mordecai is an exquisite example of what is possible when the masculine and feminine I-centers meet in mutual deference. The Talmud calls Megillat Esther the dawn of a new age and a new providence.[27] …כי בא מועד

…Let there soon be heard in the cities of Judah and the streets of Jerusalem the sound of joy and the sound of gladness, the voice of the groom and the voice of the bride…[28]

[1] לְהַרְאוֹת אֶת-אֶסְתֵּר וּלְהַגִּיד לָהּ וּלְצַוּוֹת עָלֶיהָ לָבוֹא אֶל-הַמֶּלֶךְ לְהִתְחַנֶּן-לוֹ וּלְבַקֵּשׁ מִלְּפָנָיו עַל-עַמָּהּ: ט וַיָּבוֹא הֲתָךְ וַיַּגֵּד לְאֶסְתֵּר אֵת דִּבְרֵי מָרְדֳּכָי: י וַתֹּאמֶר אֶסְתֵּר לַהֲתָךְ וַתְּצַוֵּהוּ אֶל-מָרְדֳּכָי: יא כָּל-עַבְדֵי הַמֶּלֶךְ וְעַם-מְדִינוֹת הַמֶּלֶךְ יוֹדְעִים אֲשֶׁר כָּל-אִישׁ וְאִשָּׁה אֲשֶׁר יָבוֹא-אֶל-הַמֶּלֶךְ אֶל-הֶחָצֵר הַפְּנִימִית אֲשֶׁר לֹא-יִקָּרֵא אַחַת דָּתוֹ לְהָמִית לְבַד מֵאֲשֶׁר יוֹשִׁיט-לוֹ הַמֶּלֶךְ אֶת-שַׁרְבִיט הַזָּהָב וְחָיָה וַאֲנִי לֹא נִקְרֵאתִי לָבוֹא אֶל-הַמֶּלֶךְ זֶה שְׁלוֹשִׁים יוֹם: יב וַיַּגִּידוּ לְמָרְדֳּכָי אֵת דִּבְרֵי אֶסְתֵּר: יג וַיֹּאמֶר מָרְדֳּכַי לְהָשִׁיב אֶל-אֶסְתֵּר אַל-תְּדַמִּי בְנַפְשֵׁךְ לְהִמָּלֵט בֵּית-הַמֶּלֶךְ מִכָּל-הַיְּהוּדִים: יד כִּי אִם-הַחֲרֵשׁ תַּחֲרִישִׁי בָּעֵת הַזֹּאת רֶוַח וְהַצָּלָה יַעֲמוֹד לַיְּהוּדִים מִמָּקוֹם אַחֵר וְאַתְּ וּבֵית-אָבִיךְ תֹּאבֵדוּ וּמִי יוֹדֵעַ אִם-לְעֵת כָּזֹאת הִגַּעַתְּ לַמַּלְכוּת: טו וַתֹּאמֶר אֶסְתֵּר לְהָשִׁיב אֶל-מָרְדֳּכָי: טז לֵךְ כְּנוֹס אֶת-כָּל-הַיְּהוּדִים הַנִּמְצְאִים בְּשׁוּשָׁן וְצוּמוּ עָלַי וְאַל-תֹּאכְלוּ וְאַל-תִּשְׁתּוּ שְׁלשֶׁת יָמִים לַיְלָה וָיוֹם גַּם-אֲנִי וְנַעֲרֹתַי אָצוּם כֵּן וּבְכֵן אָבוֹא אֶל-הַמֶּלֶךְ אֲשֶׁר לֹא-כַדָּת וְכַאֲשֶׁר אָבַדְתִּי אָבָדְתִּי: יז וַיַּעֲבֹר מָרְדָּכָי וַיַּעַשֹ כְּכֹל אֲשֶׁר-צִוְּתָה עָלָיו אֶסְתֵּר:

[2] כתם אופיר מבואר ומפורש (כ”א) – פתח השער: דרכי ביטול הגזרה: כמה דרכים בביטל הגזרה, וסכנת עליה ביחודים. כתם אופיר מבואר ומפורש 4:4

[3] כ”א 4:1-3.

[4] כ”א 4:5.

[5] כ”א 4:8.

[6]כ”א 4:11.

[7]כ”א 4:15-17.

[8] כ”א 4:17.

[9]כ”א 4:16.

[10] Leshem, HDOH 2:4:20:4/5

[11] If you spell anochi out in full, with the vav that is contracted and instead appears as the cholem above the nun (which is the only way the word appears in the Tanach). But if you add the vav in full (אנוכי), then anochi spells, ani (I am) 26 (אני כ”ו) (ie the gematria of the Tetragrammaton). And it also spells א/להים (86) plus its kollel (ie, 86 + 1 = 87 = אנוכי).

[12] Leshem, Hakdamot v’Shearim (HVS) 4:5.

[13] HVS 7:5.

[14] This is a teaching that R. Isaac Luria (the Ari) states repeatedly throughout his work. To site just one instance: Aytz Chaim, Heichal Nukba, Shaar Miyut HaYareach, chapter 1.style=”font-family: ‘trebuchet ms’, geneva, sans-serif; font-size: 10pt;”>[15] ספר הדע”ה דרוש מיעוט הירח סימנים ט’ וי’

[16] Ibid.

[17] אם רצונך שלא תמות, מות עד שלא תמות…פירוש שימית את תאותו לכל ענינים הגשמיים כשהם לעצמם, ולא יראה בהם שום חשיבות ושום תועלת אלא במדה שהם משמשים לתכלות היחידה—העולם הבא.

[18] Psalms 109:4.

[19] Gen. 3:20.

[20] HDOH 2:4:20, 21

[21] Daat elokim, 144; כ”א 4:11.

[22] כתם אופיר מבואר ומפורש (כ”א) 4:11, הערות רכ”ד

[23] כ”א 5:2..

[24] Megilat Esther 5:4.</span

[25] TB Chagiga 14b.

[26] HDOH 2:4:22.

[27] TB Yoma 29a.

[28] From the 7th marriage blessings, which quotes from Yirmiyahu 7:35 (and others). See Kabbalistic Writings on the Nature of Masculine and Feminine, Chapter 8, for R. Shneur Zalman of Liadi’s extensive (and radical) commentary on these words.