Pesach 2015 / 5775

Pesach 2015 / 5775

Based on R. Tsadok HaKohen, Tsidkat HaTsadik #218

Sarah Yehudit Schneider

Between Barekh and Hallel (stage 13 and stage 14 of the seder)—between thanking HaShem for the meal (Barekh) and thanking HaShem for our freedom (Hallel)—there is a mysterious interval that revolves around the pouring of Elijah’s cup. We fill a goblet with wine, open the door to welcome Elijah the Prophet~Angel~Harbinger-of-Mashiach, and recite verses that urge HaShem to destroy evil.

Who is Elijah? What does he have to do with this point in the seder? Why do we recite verses of vengeance when he arrives?

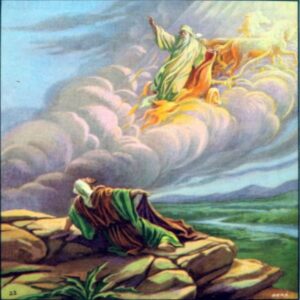

Elijah was a zealous prophet known for defeating the idolatrous Priests of Baal in a dramatic showdown on Har Carmel;[1] and for transcending death by ascending to heaven in a fiery chariot,[2] as recorded in the Book of Kings.

Legend has it that Elijah is a kind of avatar who materializes and de-materializes at will. He appears to mystic scholars and transmits secrets from the inner planes. He appears to spiritual seekers as an outcast to test the integrity of their compassion. He appears at circumcisions to bless the newborn. And he appears at critical moments in different guises to rescue people from harm (or to shift their trajectory toward good). Charbona (in the Purim story) was Elijah in disguise.

Elijah also plays an active role in the messianic end of days. Embodied in one form or another, he will prepare the infrastructure to accommodate this massive paradigm shift that will occur on both the inner and outer planes. His tasks include: restoring the chain of ordination, reconstituting the Sanhedrin, answering the Talmud’s unresolved questions,[3] correcting mistaken rulings. And then, of course, it is Eliyahu’s job to announce Mashiach’s arrival and to anoint him.

But really, concludes the Mishna, Elijah’s primary role is to institute world peace.[4] It is no coincidence that the cue for his appearance in the evening’s seder is the haggadah’s only mention of peace, for our Birkhat HaMazon concludes with the word shalom. We then bless and drink the third cup, fill Elijah-the-Peacemaker’s goblet, welcome him to the seder, and recite verses that, paradoxically, invoke what seems to be the opposite of peace.

R. Tsadok explains that Elijah’s appearance at the end-of-days, is more a state of consciousness, than an individual performing specific tasks. Certainly one does not preclude the other. It is possible that Elijah materializes when the generation is ready. It is also possible that the generation gets ready when Elijah appears on the scene.

Either way, says R. Tsadok, biyat Eliyahu (Elijah’s pre-messianic return) marks a milestone in our multi-millennial pursuit of enlightenment. Adam and Eve contained the souls of all humanity. We all agreed with the decision to eat from the Tree of Knowledge and we all suffered the shattering (and diminishing) consequences of it. The lust for pleasure snaked its way into our psyche and wangles us to make short-sighted decisions that indulge its reckless appetite. The situation quickly deteriorated and by the next generation (with Kayin and Hevel) envy, spite and power-lust appear.

According to kabbala, the yetzer for pleasure associates with the right (and watery) pillar of chesed which (when lacking moral fiber) veers toward self-indulgence. The yetzer of anger, power, control and domination associates with the (fiery) left pillar of gevurah (translated, variously as might, justice, or discipline). The latter, says R. Tsadok, is the more virulent of the two, and the hardest to reform.

It does not work to fight fire with fire, says R. Tsadok. The purity of soul required to employ righteous anger against evil and to do so without a trace of pomposity is beyond our capacity at this stage of development. We cannot whitewash our midah of anger by directing it toward a righteous cause. Inevitably, the ego will steal illicit gratification despite the virtue of its mission. It’s impossible, says R. Tsadok, to fully rectify the yetzer of power at this time. We may learn to contain it when necessary and express it when appropriate, but we cannot (yet) transmute it entirely.

The final tikun of our fiery yetzer depends upon a previous attainment—the cleansing of our desire nature (the other yetzer of taava). R. Tsadok borrows a term from tefillin to explain their interdependence. The tikun of anger, says he, requires a guf naki—a clean body, but in this sense, a purified will that genuinely (instinctively) prefers the most good-serving option in every moment. Otherwise the ego will puff from its laurels and we’ll lose ground even while we gain it.

And that brings us to the prophet Elijah, who left this world in a fiery chariot—who ascended but did not die. The Zohar declares: “there is no death without sin.”[5] Eliyahu is the only one mentioned in the Bible to have escaped death, which means that he must also have escaped sin, which means he must have achieved a guf naki (a purified desire nature). Eliyahu becomes the archetype of righteous anger—and its only role model. As long as evil exists in the world there is a need for the yetzer of anger and belligerence…even if our channeling of that energy lacks precision and pure intention. And even though it generates collateral damage and spiritual debts that will need to be paid. And even though it contributes to the problem that it seeks to eradicate. Still, in the interim, it serves a necessary function…it holds the perpetrators of evil at bay.

Eventually we will need to eliminate the yetzer of vengence altogether, for it has no place in the messianic age. Its function is to negate that which negates God. But in messianic times, there will be no negation of God. Truth will shine unobscured and there will be no place for holy outrage.

But there is an intermediate step between here and there, and that is the rectified expression of anger. We need to fix it before we can let it go. We need to become transparent channels of HaShem’s wrath without taking personal gratification from that privilege. That is what we practice year after year on seder night when we invite Elijah to the table and speak words of indignation toward all that opposes truth and justice, God and good.

World Peace requires the dissolution of evil if it is to endure. The challenge is to battle its depravity without also contributing to it. Even when outrage is appropriate, and defiance is right, if our ego inflates from the conquest, we produce the underpinnings of the very evil that we seek to squelch. The problem is not our show of anger, but its cooptation by the ego.

Elijah is our mentor of rectified fury. When the midrash reports that he’ll “appear” at the end of days, it is teaching, says R. Tsadok, that we (as a nation) will manifest Eliyahu’s virtue, for (paradoxically) that is what it will take to institute world peace. The messianic peacemaker must salvage every sliver of light, but he/she/we must also recognize the irredeemable obstacles to peace and eliminate them…and do all of this without a trace of gloating. If the peacemaker’s anger is truly transpersonal, then it also partakes of HaShem’s pain (so to speak) in its necessity.[6] Yet it also does not shrink from that necessity.

It is possible, says R. Tsadok, to touch this place of righteous anger even if we can’t sustain it. Let it be that on Pesach eve, when we open the door to Eliyahu-the-Zealous-Peacemaker that his spirit descend upon the nation and inspire us, from the inside out, to recite these verses with the very same intention that he would bring to them. And may the purity of that moment bring Mashiach NOW!

————

[1] I Kings 18.

[2] II Kings 2.

[3] This is the basis for another explanation for this portion of the seder: The four cups correspond to the for terms for redemption in the verse, Ex. Xxx”xxx. Yet really there are five terms for redemption in that passage. So perhaps we should drink five cups (instead of four). The question remains unresolved. Maybe yes, maybe. So as a compromise, we pour the fifth cup but do not drink it, and wait for Eliyahu to come and clarify the matter for us.

[4] Mishna, Edyot 8:7.

[5] Zohar, Bereshit, 57b

[6] Taanit 16a; Megilla 10b and Sanhedrin 39b.