Shavuot 5778 / 2018

Shavuot 5778 / 2018

Sarah Yehudit Schneider

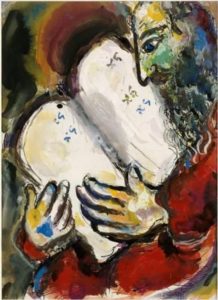

“And you shall know the soul of a convert // because you were strangers in the land of Egypt.” [Ex 23:9]

All HaShem’s secrets are buried in the Torah, though they’re concealed behind many obscuring garments. The wise, who are full of eyes, can find the secrets hidden there.…In numerous places the Holy One cautions us to not oppress the convert…In one of those places a great secret emerges from its sheath in the first half of the verse—And you shall know the soul of a convert…—and hides immediately in the second half of that verse—for you were strangers in Egypt. The first phrase exposes a deep secret, while the second phrase presents a mundane explanation that diverts the reader’s attention from the mystery that was just revealed. [Zohar 2:99a]

Our Written Torah is fixed and final. Its sequence of letters, spacings, stories and commands is sacred and static. Its authority derives from its constancy. Our Oral Torah is the opposite—it is always changing and expanding. Not a second passes that does not leave it enriched by some new insight discovered in that moment somewhere on the planet. The Oral Torah comprises two parallel tracts: an authoritative chain of rabbinic commentary, along with a vast treasury of creative insights pressed from the hearts of Jews striving to live with integrity to the truths they absorbed at Sinai.

Focusing on the rabbinic portion of the Oral Torah—it is curious to note that converts (or children of converts) have made a disproportionate contribution to its authoritative documents:

The source of an anonymous Mishnah is R. Meir; an anonymous Tosefta is R. Nehemiah; an anonymous Sifra is R. Judah; an anonymous Sifre is R. Simeon. And all of these express the views of R. Akiva [who was their teacher].[5]

Akiva’s father was a convert who descended from Sisera, the general who sought to annihilate the Israelites in the period when Devorah judged.

Tsadok attributes this disproportionate involvement of converts in formulating the Oral Torah to their work ethic and seasoned expectations. He explains that since converts had to work to become Jewish, they are accustomed to toil in their spiritual life, and expect nothing less. They overcame enormous obstacles in their conversion process. Consequently, they do not balk at the labor required to generate Oral Torah and the arduous demands of its rabbinic fences that are exponentially beyond the Written Torah’s ultimatums. Born-Jews can get away with being lazy—accepting things at face value, resting on their ancestry (yichus), languishing in their comfort zone.

R.Y.Y.Y. Safrin (the Komarna Rebbe) explains this curious phenomenon kabbalisticly. Commenting on the Zohar’s explication of the verse, “…And you shall know (דעת) the soul of a convert…,”[Exodus 23:9] he explains:

All the unifications (יחודים) that you perform [to unite heaven and earth, to repair fragmentation, to draw blessing into the world, to reveal the hidden oneness of God[8]] …they all employ higher daat (דעת) [the meditative faculty that joins head with heart to produce the internalized knowing that is a euphemism for sexuality[9]] … and they all require partnership with the “soul of a convert”….[10]

The idea is that converts bridge worlds—they started as outsiders and found their way in. A wall is no barrier to them. Their talent for transcending boundaries, by knowing the inside truth of both sides, is a resource that benefits us all, suggests R. Safrin. Whether we are seeking to unite with a partner in marriage, or to access an encounter with the Divine, or to pull heaven down to earth, or connect a truth back up to its root…these are all yichudim which require, by definition, the bridging of worlds. Success takes teamwork, says R. Safrin. We need help from the “convert” to negotiate the tricky border-crossings that are part and parcel of yichudim.

Just like in the human body there are some organs (like heart and liver) that occupy a specific place. Yet, there are other “organs,” like blood or lymph, that have no fixed “place.” They circulate through the entire body, transporting substances from one place to another. For example red blood cells pull oxygen through the lung tissue barrier, carry it to a distant locale and then facilitate its passage through the walls of those distant cells. The blood then pulls the waste (CO2) out through the cell’s wall and carries it back to the lungs where it passes through numerous barriers until it’s expelled by an out-breath.

The souls of converts serve a similar function in the spiritual realms (says R. Safrin). They facilitate:1) soul-ascents into higher states of consciousness, 2) descents whereby a soul from the inner planes contacts the physical world, and 3) all the border crossings that these (and other) yichudim entail.

This term, soul of a convert, has a literal, psychological and kabbalistic association.

Literally, it refers to the people that convert to Judaism—the proselytes who start as non-Jews and enter the fold by choice. Their transit from outside to in leaves a thread of connection in its wake. If our job is to shine the truth of Divine Oneness out to the world we must heed the Zohar’s advice: Only a vessel that integrates the entirety of creation into a single universe encompassing entity below can hold this revelation of Oneness without shattering. The threads (left by converts) connecting Israel to the nations become infrastructure that will enable this final, cosmic yichud.

Psychologically, we all have an inner convert, a part of us that is not yet infused with faith. It’s our inner truth-seeker whose doubts and questions are real and fair. They rattle our soul and in the pursuit of answers our consciousness expands, our faith integrates and our heart wisens. The inner sceptic, now convinced, crosses the river and (metaphorically) converts.

The Talmud declares: “You don’t fully own a truth unless you first stumble over it.”[11]

The pursuit of truth instigated by the inner convert generates the creative insights that become our contribution to the Oral Torah. The deepened relationship with HaShem enabled by this “conversion” is a yichud in its own right.

Kabbalistically, the souls of converts, in their afterlife, circulate through the inner channels that connect the seven heavens. In this role they facilitate the yichudim that are happening 24/7 on the inner planes as souls rise and fall depending upon their state of merit or the cycle of holy days or their active connection (called ibur) to souls on the earthly plane. The Zohar teaches that when a soul enters a heavenly chamber it must be properly attired, meaning that its garment of light must resonate with the frequency that characterizes that particular plane of consciousness. And this garment (called chaluka d’rabanan) is a visual embodiment of the Oral Torah generated by the thoughts, speech and deeds of its life. That garment, which enables the soul’s passage from outside to in, is supplied (says the Zohar) by the soul of a convert (nefesh hager).

Praised be to the Torah and its wellsprings of wisdom that has sustained us as a people for millennia! And praised be to the converts, the unsung heroes, whose contributions to our Oral Torah, past and present, enrich both our lives…and our afterlives.

חג שמח

——

[1] Rashi cites Targum Onkeles 50 times in his commentary on the Torah.

[2] Drew Kaplan, “Rabbinic Popularity in the Mishnah VII: Top Ten Overall [Final Tally] Drew Kaplan’s Blog (5 July 2011).

[3] TB Gittin p. 4a; TB Horayot 13b-14a

[4] TB Gittin 56a

[5] TB San 86a; TB Yevamot 62b

[6] Rashi on TB San 31b; Shmot rabba 1:30; Yalkhut Shimoni, Shmot 2: רמז קסז; Sefer Charedim, perek 3; TB Megilla 13a; Zohar 3:167b.

[7] Zohar 3:261a , Shulchan Aruch 428:6 sk 18, TB Meg 31b

[8] Netiv Mitzvotecha, Netiv HaYichudim, Peticha. The Komarna Rebbe presents a definition of yichudim there.

[9] Daat (integrated knowing) is a euphemism for sexuality based on Gen. 4:1. “And Adam knew Chava, his wife, and she conceived…”

[10] R.Y.Y.Y. Safrin of Komarna, Zohar Chai 2:99a, “ואתם ידעתם”.

[11] TB Gitin 43a.